Michel Baudin, who most assuredly has forgotten more about lean than I’ll ever know, wrote recently about the “personal kanban” and concluded that it was much ado about nothing on three counts. First, Baudin argued that it was essentially old wine in new bottles—the Scancard System of the 1980s did much the same thing. Second, its lack of portability makes it impractical to use in meetings or with a network. Finally, it only displays the current status of a project, rather than the whole history. (In a felicitous turn of phrase of which I’m really jealous, he also called it “a feat of vocabulary engineering,” leveraging the buzz around an aspect of Toyota’s production system to repackage ideas that have little to do with it.)

Having just written about value of a personal kanban in my forthcoming book (A Factory of One, available in mid-December), and having seen many individuals apply the concept successfully, I must respectfully disagree.

He’s absolutely right that for a long time now people have known they should limit their work in process. However, the unhappy fact is, they don’t—and it’s not just because supervisors insist on piling more and more projects onto hapless subordinates, like Egyptian slave masters in The 10 Commandments. In large part, people don’t limit their WIP because they have no idea themselves of how much work they have on their plates. Particularly in a modern office, most of their work is invisible, residing in electronic files, email messages, and all manner of stray bits and bytes on their computers. As a result, people are terrible managers of their own workload, and they reflexively accept new responsibilities and commitments when they’d be far better off saying “no.” The personal kanban, like the Scancard before it, does a wonderful job of making that work visible and helping people better manage their work.

Baudin’s comment about the lack of portability is valid, but in my opinion hardly disqualifies the personal kanban as a valuable tool. Much of a knowledge worker’s time is spent in the office, not a conference room, and is therefore accessible to him or her when needed. And besides, if the kanban in the office encourages people to have their meetings where the work is done, and not in the conference room, so much the better.

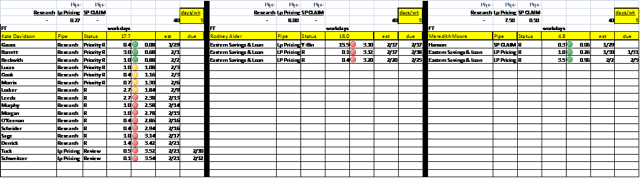

His final point about the kanban only displaying the current state of a project can be easily fixed. Beneath the “Backlog/Doing/Done” section, you can map out the key steps of the entire project/value stream, as you can see in the photo below.

This section provides the context for each task—both the history and the future requirements, the latter of which the Ybry Chart can’t do.

The last thing I’ll say in defense of the “personal kanban” is this: the purpose of a kanban in a factory setting is to control WIP and pull resources forward at the right time. The personal kanban does precisely that—except that the resources in this case are the person’s time and attention. If the whiteboard and sticky note combination of the personal kanban succeeds in this goal, then I think it deserves the name kanban.

So, Michel, while the personal kanban may not be a breakthrough on the order of, say, Copernicus’s insights on planetary alignment, I maintain that it’s a valuable, capable, and flexible tool to improve knowledge worker production.