[Note: this article was originally published at The Leadership Network.]

He’s one of the most decorated quarterbacks ever to play the game. Indeed, six Super Bowl appearances, four wins and two Most Valuable Player awards have assured Tom Brady his place in the pantheon of football greats. He can also teach you about standard work.

Tom Brady, the quarterback for the New England Patriots, is unquestionably one of the greatest football players of all time (and as a lifelong New York Jets fan, growing up in a family of Jets fans, you have no idea how much it pains me to admit that). Brady is also remarkably durable: aside from losing a full season for knee surgery, he’s missed only one game during his 15-year career. Yes, he’s talented. Yes, he’s surrounded by skilled players who both protect him and catch his passes. Undoubtedly, he’s lucky as well. But Brady’s success is also due to an unbelievably methodical, structured approach to skill development and physical fitness. A profile of Brady in Sports Illustrated explains his process this way:

Brady is a quarterback whose daily schedule, both in and out of season, is mapped clearly into his 40s. Every day of it, micromanaged. Treatment. Workouts. Food. Recovery. Practice. Rest. And those schedules aren’t just for this week, this month, this season. They’re for three years. That allows Brady and [Alex] Guerrero [Brady’s body coach] to work in both the short and long terms to, say, increase muscle mass one year and focus on pliability the next. “The whole idea is to program his body to do what we want it to do,” says Guerrero. “We don’t let the body dictate to us. We dictate. Everything is calculated.”

. . . The in-season portion of his regimen is designed to run through Super Bowl Sunday; if New England’s campaign ends in a playoff loss. . . Brady completes every drill, every throw, anyway.

That’s their system. From the outset the principles made sense to Brady, who had spent the early part of his career like most athletes. He’d worried about injuries after they happened. He’d focused on rehabilitation as opposed to preventative maintenance.

If this doesn’t epitomise standard work, I don’t know what does.

Building—and leading—an organization requires a similarly structured approach to work. And yet, most leaders don’t have this kind of structure in place. Many haven’t identified what their high-value activities are, and fewer still reflect upon how they’ve actually spent their time during the year. Their calendars are largely filled with standing meetings, obligatory travel, and corporate events, with the balance of the time dedicated to fire-fighting and email management. Most executives don’t even have a clear plan of how they want to spend their time each year, aside from a vague and wistful sense that they’d like to spend less time in meetings, and more time thinking deeply about where they want to take the company.

Of course, building and leading a fit enterprise is much more challenging than maintaining a fitness program, no matter how scientifically complex it is. Take Brady’s strict regime for example. A freak injury may derail his training, but ruptures and tears aside, his plan is relatively easy to follow providing he maintains his discipline throughout.

There’s a temptation to think that a manager’s (to say nothing of a higher level leader’s) job is too complex to define best practices, that the issues he grapples with are so fluid and so diverse that the job necessitates constant improvisation and adaptation. There can’t be best practices for a leader.

That’s flat-out wrong.

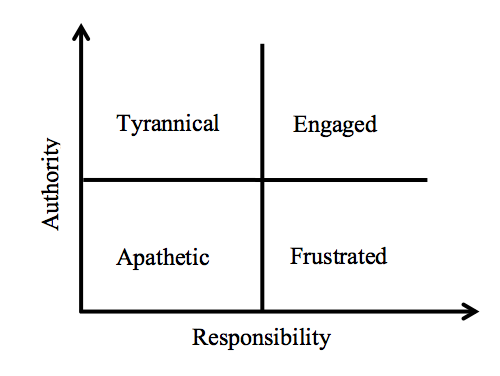

Standard work for a leader doesn’t look like the detailed job instructions for someone working the fryer at McDonalds. A leader’s work is highly variable, and often chaotic. But it’s nonetheless possible to create pockets of stability within the chaos. Indeed, leaders hoping to achieve Tom Brady’s level of excellence need to create and deploy standard work at all levels of the company. Just as Brady would have struggled to stay healthy and reach his staggering level of excellence without following his standard work, so too will a leader fail without standard work. That means the leader has fixed times to walk the shop floor so that she can see the work being done, learn about improvement projects underway, and provide coaching on structured problem solving. It means discussing quality, safety, cost, delivery, employee morale, daily stats and targets with his team. It means actually working shoulder to shoulder with employees to more deeply understand what they’re dealing with, so that he knows what needs to be improved.

Making these types of activities standard ensures that the leader’s work gets done the right way, at the right time. Beyond that, it serves to double check that the tasks she spends her time on are the tasks necessary to support the organization’s strategic goals, not just the daily “administrivia” that chokes so many leaders’ days.

So next time you tune into a New England Patriots game, keep a close eye on Tom Brady. Watch how he methodically surveys the field. Notice his practiced footwork. Witness the controlled precision of his movements. Observe the trajectory of the tightly spiralled ball as it finds its target—and marvel at the countless hours of disciplined practice, the standard work, that makes it all possible.