Responsibility Without Authority

My friend Sara runs a rapidly growing non-profit in NY. They’ve gone from 5 employees to 55 in the past 18 months. Despite the increased staff, decision-making is more sclerotic than ever, she and her executive team are still consumed with trivialities, and wide-spread frustration is growing over the organization’s lack of nimbleness.

Her situation reminded me of a story I heard about James Treybig, the president of Tandem Computers. He once called a meeting with the engineering leadership team to find out why, when there were 20 people in engineering, the team regularly performed miracles. But three years later, with 300 people in engineering, it seemed like nothing was getting done.

Probably you’ve seen the same thing in your own organization—yet I don’t think that this is an immutable fact of life, on par with Newton’s Laws, or the impenetrability of your medical insurance EOB statement. And while I can’t speak for Tandem, in Sara’s case, the problem definitely isn’t due to a bloated organization loaded with corporate fat.

The truth is that when responsibility doesn’t equal authority, you’ve got problems. Sara beefed up the organization in order to relieve the exec team of the burden of dealing with the innumerable small, daily decisions that devour time like the Eighth Plague: which type of desktop inboxes to buy. Which water bottle style to give away at a fund-raising event. Where to host the holiday party. Whether to use royal blue or slate blue for highlight trim. She wrote job descriptions that specified responsibility for managing these decisions, and hired people for the positions.

Sounds good. Except that the job descriptions didn’t explicitly give them the authority to make these decisions. Further, she didn’t coach the leadership team to delegate that authority. The predictable result? The myriad daily issues still come bubbling up to the leadership team’s level—but now each decision takes even longer, because approval for each one requires a meeting between a senior leader and her subordinates. Slower decisions and more time sucked up in meetings: a double loss for Sara.

In some ways this situation is a more nefarious version of the founder’s dilemma—in which an entrepreneur’s stranglehold on decision-making, so helpful in launching a company, ends up impeding its long-term growth. Sara’s situation is worse because it looks as though she’s avoiding the problem—after all, she’s just hired a bunch of people to handle these decisions. Unfortunately, she’s only exacerbated the situation by increasing headcount and impeding execution.

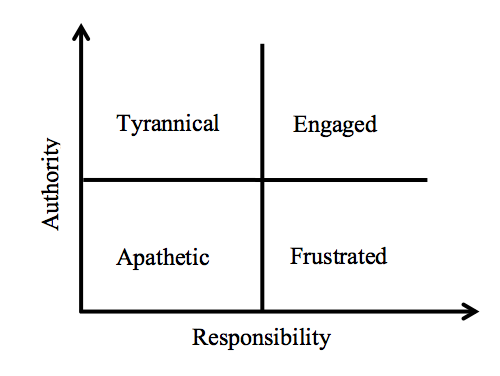

At Sara’s organization, the mismatch between responsibility and authority created bottlenecks. But this kind of mismatch between authority and responsibility typically creates different kinds of problems throughout an organization:

- Low Responsibility, Low Authority: here’s the classic recipe for apathetic, demotivated workers. Customer service people who don’t have the power to solve problems. Assistants who don’t get one-on-one time with their execs. These are the people with glazed eyes waiting for the five o’clock bell to ring, who have no energy or desire to help improve the company.

- High Authority, Low Responsibility: here’s the blueprint for installing a tyrant of minutiae. The person in finance who insists that you fill out your travel expense form in blue ink, not black—or for that matter, that you use their form, instead of your spreadsheet version of it that does the math for you. The person at the DMV counter who sends you to the back of the line because you forgot to put your middle initial on form 2976A/3. These people make life miserable for everyone and will never leave, because they’ve built a comfortable empire.

- High Responsibility, Low Authority: this is Sara’s world—the grey world of frustrated strivers. Nurses who can’t make changes to procedures that would allow them to spend more time with patients. Product developers who are told to just make what the sales department demands. You can find these people polishing their resumes as they look for another job.

- High Responsibility, High Authority: this is where you want to be. They have responsibility for a job, and the authority to accomplish it. These people are able to contribute to growth, improve performance, and move the organization forward.

Here’s the thing: the apathetic, the tyrants, and the frustrated—they could be anyone in the company. The engaged, committed workers are no better than the others. They’re just in jobs that allow them to exercise autonomy, achieve their goals, and strive for greatness.

Ceding ownership for decision-making is hard, but totally worth it. Sara and her executive team are now rewriting job descriptions to better match responsibility and authority. It’s an uncomfortable process, because it means yielding ownership of issues that they’ve always handled. But they’re already starting to see faster execution, higher morale, better collaboration among departments, and a drop in the number of meetings they need to attend.

Take a look at your direct reports: do they have authority commensurate with the responsibility you’ve given them? If not, it’s worth the time to revisit their jobs and see if you can bring those two components into balance.