I'm a rabid believer that lean concepts and tools can improve personal productivity enormously -- hell, I (literally) wrote the book on that. But it's nice to see validation from the go-go world of internet startups.

Bill Trenchard, founder of LiveOps and now partner at First Round Capital, just published a piece that supports my argument. He believes that 70% of a tech CEO's time is spent sub-optimally, and his countermeasures come straight out of the lean playbook.

Creating Standard Work: Bill suggests identifying the core processes -- which are often repetitive -- that drive the company, and creating standard work around them.

For anything you do more than three times, write down your process in detail. Build playbooks that you can hand off to someone else, so they can execute something exactly the way you would. Never get held up by people asking what the next step is or whom they should ask about a process.

This is how Uber in particular scaled so quickly. They’ve grown to over 70 cities and they’ve killed it in all of them. How did they do it? With a playbook. They have a list of the things they do in every single city when they launch, with slight regional adjustments. They have practiced this method and tested it and wrote it all down. So now they just execute, like turning a key.

The startups that I have seen succeed the most at scaling are the ones who have systematized their common actions and core procedures early, and made a habit of it as they grew.

Reducing the Waste of Over-processing: Bill takes on the always thorny issue of managing email and sees stupendous over-processing waste in the way we read and re-read our messages:

Think about postal mail for a second. Do you pick your letters up, look at each one and then put them back down only to pick them up and put them down again and again? This is the definition of insanity. Yet that’s exactly what most of us do with our email.... If you can respond to or act on any email in under two minutes, just do it immediately. If it’s going to require more than two minutes, move it into your task manager to process later. When you do this, you have the ability to prioritize tasks and emails in relation to each other, and your inbox no longer owns your time.

Improving Flow: The psychological research is unanimous on this point -- multitasking doesn't work. Email interruptions, whether self-inflicted or from someone sending you a message, kill your ability to create psychological flow. How to improve the situation? Like me, Bill recommends doing it in chunks to avoid fragmenting your attention:

I recommend the batch route. It lets you focus on email when you need to, and give other tasks the attention they deserve. Constant context-switching makes you mediocre at everything.

Go and See, and Leader Standard Work: Using daily standup meetings (or something similar) as part of leader standard work so that you can identify and solve obstacles quickly is critical in the factory and in the office. Cribbing from both the agile software and lean playbooks, Bill goes to the gemba:

[One of the most productive CEOs I know] circulates the office, stopping to talk to his team members one-on-one or in small groups throughout the day. He asks them:

- What’s holding you back from getting more done?

- What are your blockers? Are there any bottlenecks or barriers I can remove for you?

- What resources or processes would let you move as fast as you want to?

Get the answers to these questions and get it done for your team. If you want them to model speed, you need to model speed yourself. Give them the help they need to do their best work in record time. Responsiveness is key.

Bill's post is a good reminder that lean concepts are not just applicable to factory -- or office -- processes. They're applicable to the way that you, as an individual, work. You can remove waste, improve quality, and increase the value you create in the time you spend at the office. It's the only truly non-replaceable resource. Use it wisely.

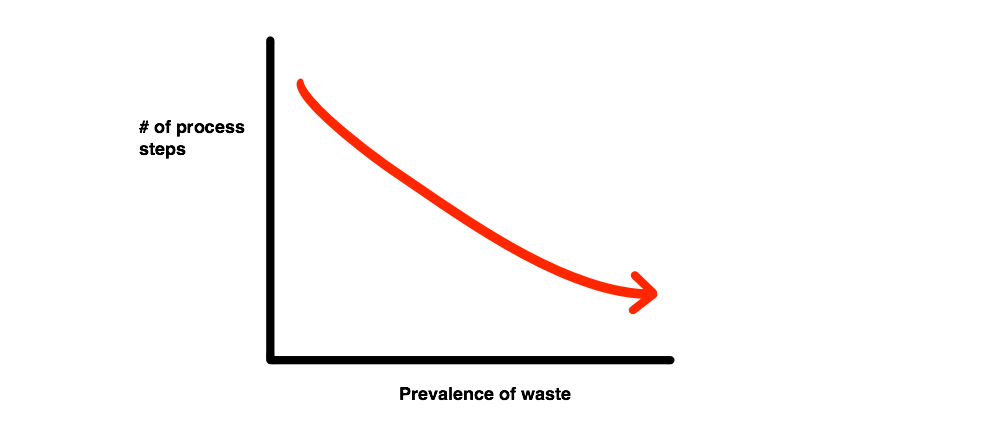

The more steps you have in a process, the more waste you'll have. No matter how smooth, efficient, and well-designed the process, more steps (and more people) means more waste.

Why? More steps means work is most likely waiting in more queues. It also means that you have more opportunities for miscommunication between people -- as Karen Martin (along with Mike Rother and Drew Locher) demonstrates, the compounding effect of even small errors in communication and handoffs causes an explosion of waste, as measured by the percent complete and accurate (%C&A) quality metric. Finally, the inevitable friction of coordinating multiple steps -- think of the emails that must be read, the low value meetings that people attend -- reduces overall efficiency.

The more steps you have in a process, the more waste you'll have. No matter how smooth, efficient, and well-designed the process, more steps (and more people) means more waste.

Why? More steps means work is most likely waiting in more queues. It also means that you have more opportunities for miscommunication between people -- as Karen Martin (along with Mike Rother and Drew Locher) demonstrates, the compounding effect of even small errors in communication and handoffs causes an explosion of waste, as measured by the percent complete and accurate (%C&A) quality metric. Finally, the inevitable friction of coordinating multiple steps -- think of the emails that must be read, the low value meetings that people attend -- reduces overall efficiency.

Download PDF to read the full article

Download PDF to read the full article