I'm very proud to say that John Hunter kindly gave me the reins (for one day, at least) for the 2011 Management Improvement Blog Carnival Annual Roundup.

What I’ve tried to do this year is select posts that gave me a new perspective about the world around me, and how improvements could be made to the current state.

What I’ve tried to do this year is select posts that gave me a new perspective about the world around me, and how improvements could be made to the current state.

First up: Shmula, the blog of Pete Abila.

Zipcar Customer Experience: Variability, Utilization, and Queueing is about as dry a blog post title as you could imagine. But what a fantastic analysis of the Zipcar system! Pete lucidly explores some of the major challenges stemming from variability and utilization facing an operation like Zipcar, and addresses the three kinds of buffers that the company needs to make it work. I’m not a process engineer, but even for me, this was one of the coolest posts of the year.

Death by a Thousand Cuts highlights how organizations begin their journey toward failure through many small decisions made over a long period of time—which is, incidentally, also how culture is created.

Pete provides a nice report on a presentation by Mark Zuckerberg in Mark Zuckerberg: I’d Rather Them Believe the Company Was Broken. If you only know of Zuckerberg from the movie, The Social Network, this is a refreshingly different view. He comes across as a modest guy who’s fully aware that his team deserves the credit for making the company successful.

Finally, check out Leader Standard Work. This concept is garnering more visibility of late. Pete provides a concrete description and approach to implementing it yourself. You’ll inevitably customize it to your specific needs, but this is a great place to start.

Next up: Daily Kaizen, the blog of the improvement folks at Group Health Cooperative.

Consultant Space Kaizen: Practicing What We Teach is a beautiful—and detailed—example of eating one’s dog food. The team describes how they applied all the tools they teach to their own workspace in order to reduce their resource consumption and model the process for the future.

Connecting to the “Why” is an excellent reminder that improvement for its own sake is pointless, uninspiring, and doomed to failure. Successful, sustainable change must be linked to the “why.” If you don’t know the ultimate purpose, then your improvement is a house built on sand.

Learning to Offer Questions, Not Solutions reminds us that change management and improvement is best led by questions, not solutions—and that those questions need to engage both the head and the heart.

The “D” Word tackles the under-appreciated trait of discipline, and explores how it’s “the fuel that drives the lean engine.”

Finally, Peter Drucker’s Management Philosophy blog. Sadly, it’s not written by Drucker himself. But the author, Jorrian Gelink, does a wonderful job of channeling Drucker’s insights, connecting them to current events, and reminding us how relevant his ideas are to both lean and management excellence.

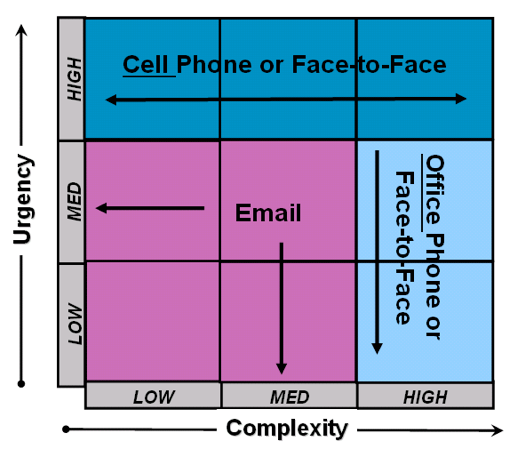

In a business world increasingly engorged with email, text messages, and IMs, Effective Communication—The Speed, Quality and Cost Triangle, higlights the very significant tradeoff between ease and quality in our communications. Read this before you send your next email.

Keeping the focus on communication, Effective Communication – Execution and Results in an Organization provides three key points to remember when communicating within an organization. Attending to these points is a good way to reduce waste and improve the quality of your communication.

How do you build trust as a leader? The Three Cores to Building Leadership Trust eloquently explains that trust relies upon execution, people development, and honesty. The are simple, but incredibly powerful truths that are too often forgotten in the drive to get through one’s email.

If you liked this curated list of links, check out the other 2011 Annual Review posts here, and the regular Management Improvement Carnival here.

I’ll slit my wrists if I have to read one more fawning article about Google’s eleven gourmet cafeterias, on-site car washes, and dry cleaning service. Or Pixar’s cereal bar (more than 20 varieties!), its lap pool, and the jungle-like cabanas and tree houses that serve as offices. Or Nike’s Olympic-size swimming pools and hair salon. Or Zappos’ life coaches.

Each of these firms was recently touted in an Amex OPEN Forum

I’ll slit my wrists if I have to read one more fawning article about Google’s eleven gourmet cafeterias, on-site car washes, and dry cleaning service. Or Pixar’s cereal bar (more than 20 varieties!), its lap pool, and the jungle-like cabanas and tree houses that serve as offices. Or Nike’s Olympic-size swimming pools and hair salon. Or Zappos’ life coaches.

Each of these firms was recently touted in an Amex OPEN Forum